For decades, Memphis’ unparalleled collection of exceptional session musicians has made it one of the nation’s top destinations for recording musicians. Some of these house bands, such as Stax’s Booker T. and the MGs, went on to become household names, while others remained relatively obscure to the general public despite their cultural contributions.

Such is the case with the Memphis Boys, the house band at American Sound Studios who cut an astounding 122 hit records in the brief span between 1967 and 1972. Composed of guitarist Reggie Young, bassists Tommy Cogbill and Mike Leech, keyboardists Bobby Emmons and Bobby Wood, and drummer Gene Chrisman, the group was fundamental in launching or rekindling the careers of some of popular music’s biggest stars, including Elvis Presley, Dusty Springfield, Neil Diamond, and Wilson Pickett.

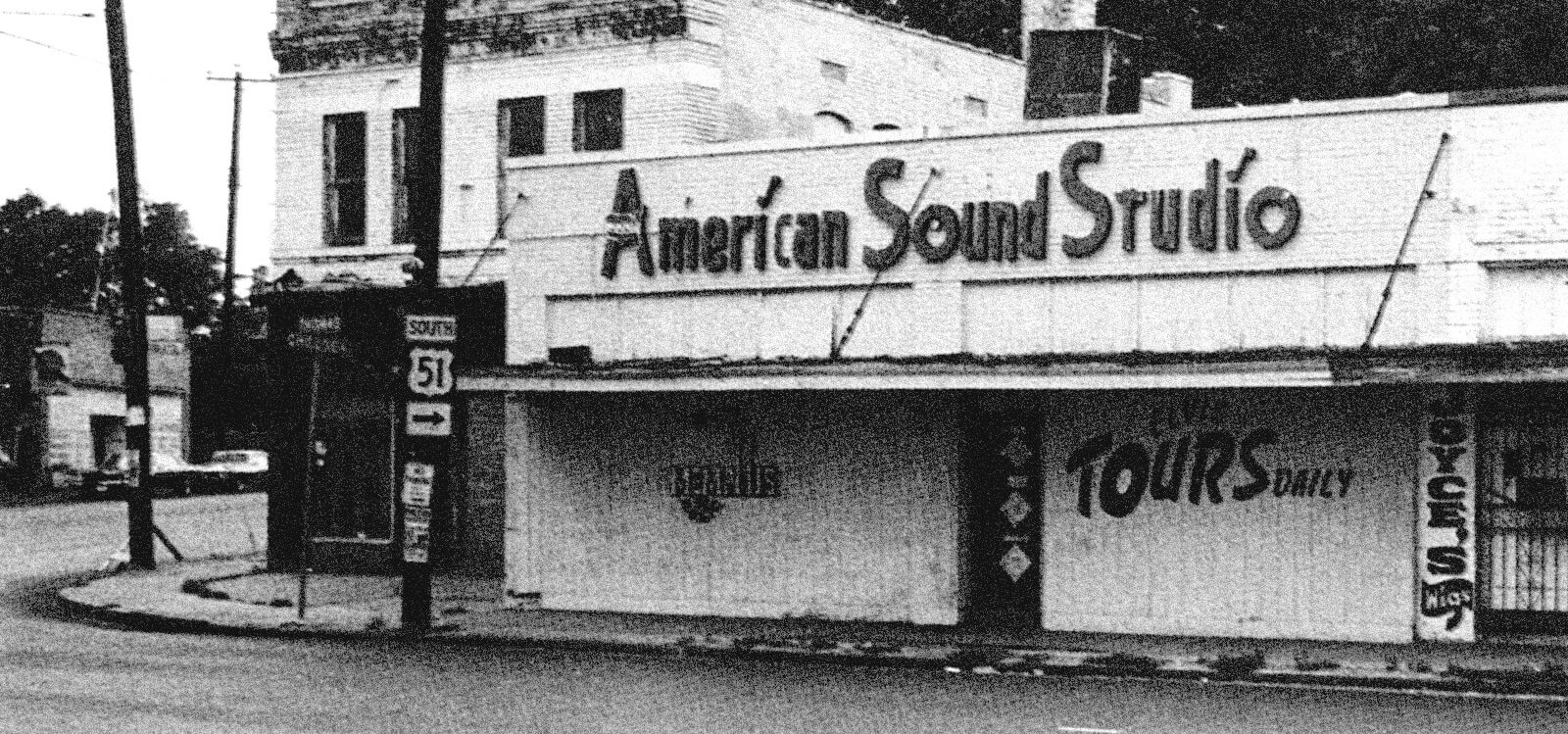

Established in 1964 by legendary producer Chips Moman, American Sound Studios was an unlikely hit factory. Housed in a strip mall at the corner of Danny Thomas Street and Chelsea Avenue in North Memphis, the studio was inconspicuous, if not a little ramshackle. As producer Dan Penn recalled, the studio’s interior reflected its façade. “Two Ampex mixers for a board, a mono machine, maybe two mono machines, and that was about it.” However, the key to the studio’s success was never about the building or the equipment within, but with the outstanding musicians who would call it home. Foremost amongst this set were American’s session musicians, a group handpicked by Moman for their top-notch musicianship and their chameleon-like ability to play with virtually any musician within any genre.

Before providing the backbone for what would eventually become one of the most successful studios in America, the musicians that would comprise the Memphis Boys had already made an impact on the city’s musical DNA. Several of the men cut their teeth at Hi Records as members of bands like the Bill Black Combo, while others got their start in the bands of former Sun musicians such as Jerry Lee Lewis and Johnny Cash. One thing that united them was their shared love of Southern music, from blues to R&B to rockabilly. “We were all from Memphis, everybody’s come up on Dewey Phillips. We knew a lot of different kinds of music,” said guitarist Reggie Young.

Originally known as the 827 Thomas Street Band (American Studio’s address), the group coalesced in the mid-1960s, originally playing together on popular songs from local acts like the Gentrys and the Box Tops . These early successes formed a natural bond among the members, also catching the eye of industry leaders near and far. Unlike other local studios like Stax and Royal, American Sound did not have a label attached to it, meaning that they were not married to particular musicians or a specific sound. Before long, record labels like RCA, Warner Brothers, and Decca began sending their artists south to record, hoping to capture some of that signature Memphis magic. Atlantic Records became a particularly important pipeline to the studio, especially after their relationship with Stax began to wane.

By 1967, Atlantic was sending most of their top soul stars to American. As producer Tom Dowd recalled, “Jerry Wexler, Arif Mardin, myself, we might show up one day with a Lulu or a Dusty Springfield and a week later come in with Herbie Mann or Wilson Pickett – it didn’t matter what artist we came in with. We knew we had an accumulation of musicians who were masters of their instruments, who were gracious and took our bizarre directions easily, who didn’t rebel, and we enjoyed their company.” Songs like Dusty Springfield’s “Son of a Preacher Man,” Joe Tex’s “Skinny Legs and All,” and Wilson Pickett’s “I’m in Love” are just a few of the smash hits that emerged from the partnerships. During its heyday, American produced 15 Top 10 hits on the Billboard “Hot 100” chart, and, by the time it closed, had produced more hit records than any other Memphis studio.

In the early weeks of 1969, the Memphis Boys faced one of their most exciting (and ultimately consequential) sessions to date. The group had been told that they would be recording with Neil Diamond, who they had worked with before on hit songs like “Sweet Caroline.” However, it was not Diamond who entered the studio that day, but rather Memphis’ most famous son: Elvis Presley. Although Presley was still basking in the glow of his successful ’68 comeback special, it had been years since he had scored a top ten single and nearly 15 years since his last recording session in Memphis. In contrast to his recent work, the sessions were largely devoid of shiny pop tunes, instead focusing on a more Memphis-centric sound incorporating soul, county, and blues. The result was some of the finest music of Presley’s career, including the iconic songs “In the Ghetto” and “Suspicious Minds,” the singer’s final chart-topper of his career.

While the crew at American Sound continued to churn out hits at a breakneck pace, the studio’s financial situation soon became untenable, forcing it to close in 1972. Moman and many of the musicians who had struck musical gold in the preceding decade wound up in Nashville and kicked off the second chapter of their storied careers. “We didn’t realize until we got to Nashville what had happened until some people started digging out the accomplishments and the charts and the hit records that we had,” said Bobby Wood. The Memphis transplants differentiated themselves from their Nashville counterparts, providing a sound that was more soulful and raucous by bringing horns, hard-driving drums, and raging guitars into the fold. Making a name around town as “the Memphis Boys,” the group proved to be instrumental in the burgeoning outlaw country scene, backing artists such as Waylon Jennings, Merle Haggard and Willie Nelson.

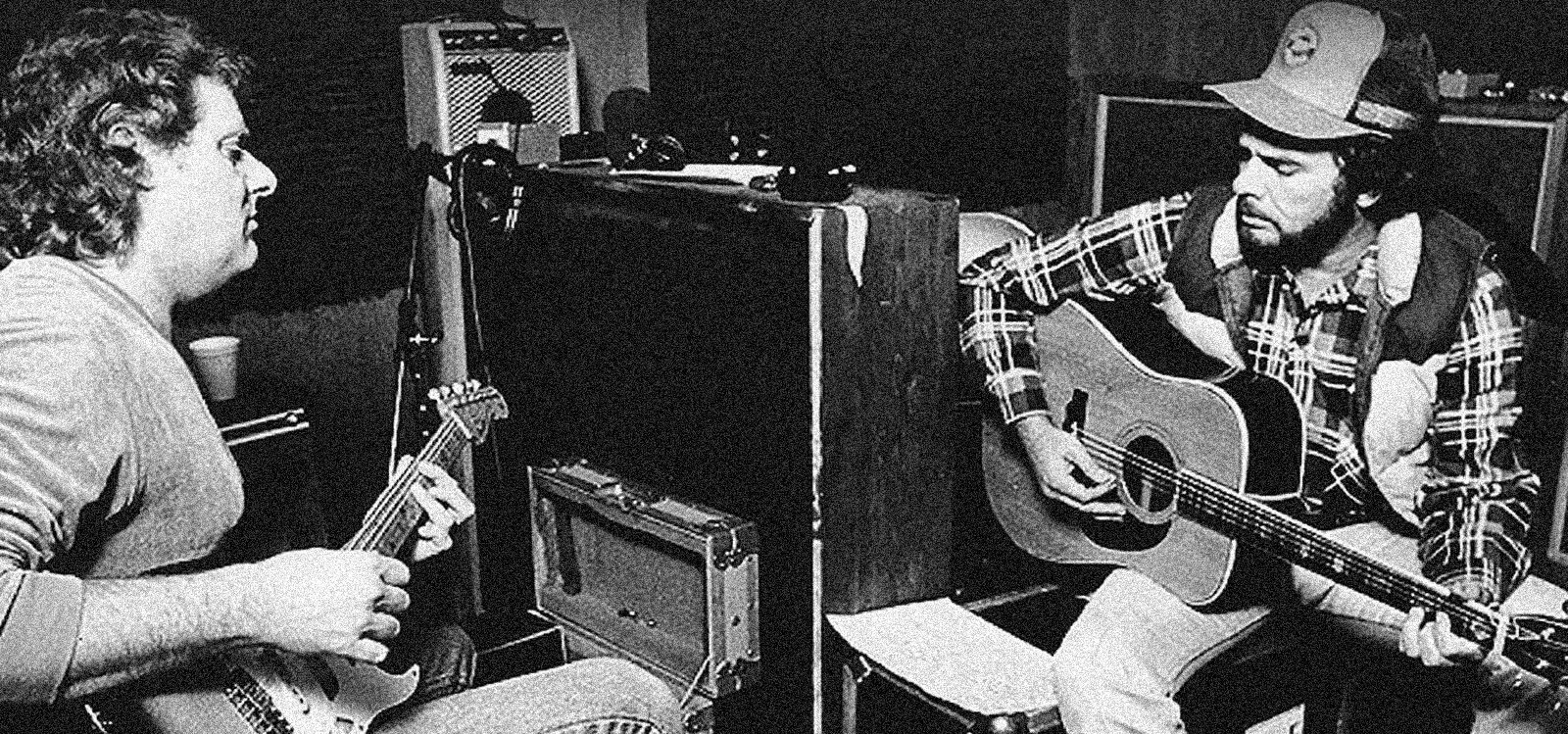

For all of their successes, the Memphis Boys have remained more out of the limelight, even to those who continue to enjoy the many classic pop, soul, rock, and country tunes they recorded. While perhaps unfair, this fact also speaks to the humbleness and modesty of the men who composed the group. “We just went to work every day,” said Bobby Wood. “People ask us why didn’t we have any more pictures, and I said we weren’t thinking about bringing a camera. We were lucky to come to work.”

Thankfully, the Memphis Boys are beginning to receive some of the much-deserved credit that has long eluded them. In 2010, author Roben Jones released her book “Memphis Boys: The Story of American Studios,” a definitive retelling of the group’s story that helped to elevate their national profile. Four years later, the group was officially recognized by the city of Memphis with the unveiling of a historical marker at the site of their old studio. At the ceremony, WEVL deejay Eddie Haskin’s summed up the group’s accomplishments perfectly, saying “Memphis music in the 20th century was a lot of things. There was blues and jazz on Beale Street in the ‘20s and ‘30s; in the ‘50s you had blues and rock and roll over at Sun; in the ‘60s and ‘70s you had soul and R&B at Stax and Hi…and at American, you had all of the above.”

Be the first to add your voice.