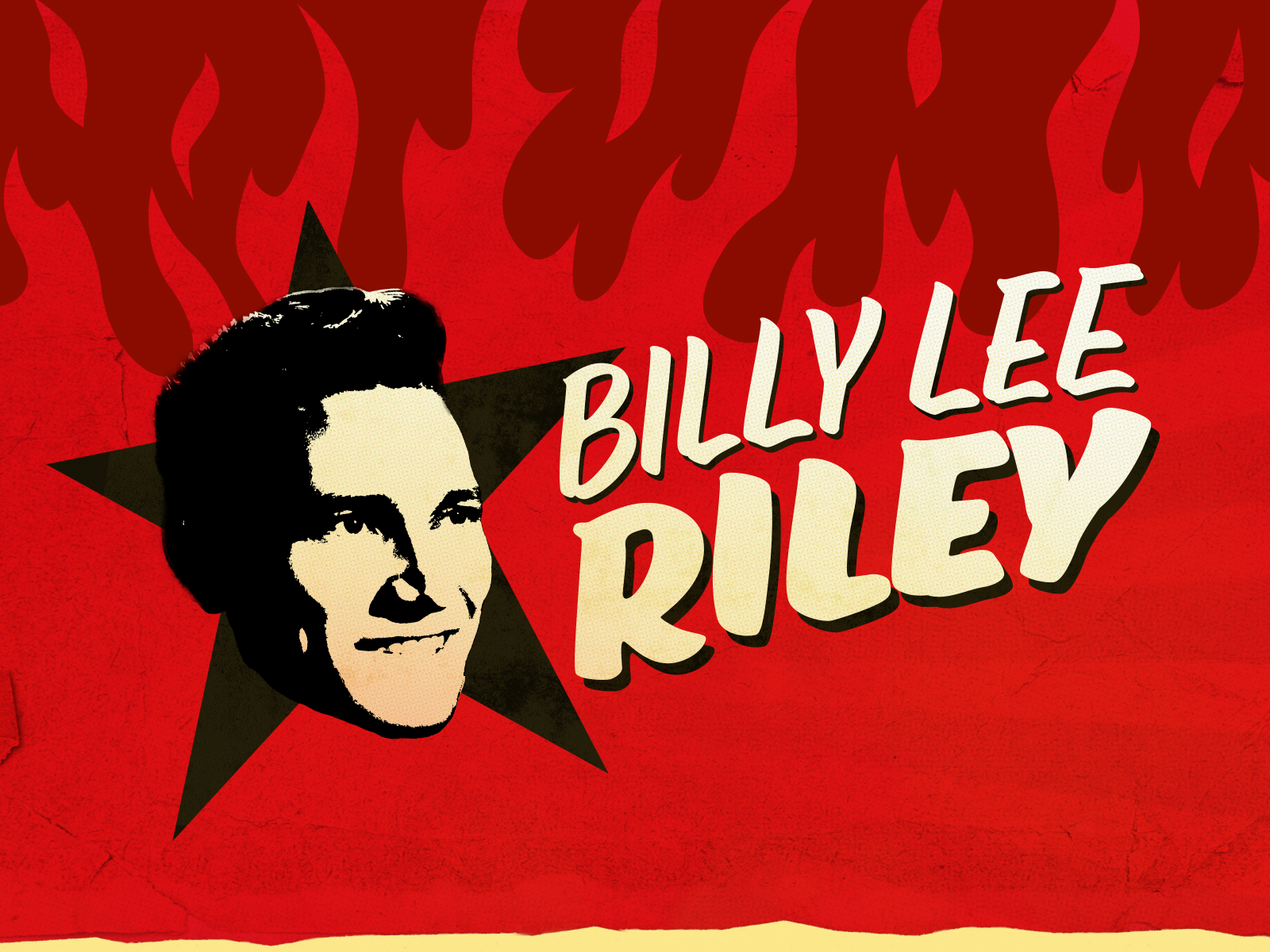

In a more fair world, Billy Lee Riley would have been an even greater superstar. Armed with the same good looks, charisma, and musical ingenuity that made his labelmates at Sun Studios household names, Riley was a true rock & roll original and one of the genre’s first unabashed wildmen, helping to set the template for the generations of rock stars that would follow him. But while Billy Lee Riley never achieved the fame and fortune of other Sun acts, his foundational contributions to rockabilly and rock & roll are undeniable. A superstar? Unfortunately not. An icon? Without a doubt.

Born in Pocahontas, Arkansas in 1933 to sharecropping parents, Billy Lee Riley’s childhood was largely defined by two things: cotton farming and music. Given the nature of their work, the Rileys moved frequently from one small Arkansas town to the next. “We lived on plantations where black and white people worked together,” Riley recalled. “We didn’t see color. We lived together, we played together, we visited each other, all on one big farm with a bunch of integrated people.”

While working in the cotton fields, Riley was exposed to the blues at an early age. “When I was very young, that was the only music that I heard,” he said. “The only music you heard on radio back in those days was hillbilly and pop music – and we didn’t have a radio. So the only music I heard was from the people who were actually playing it, sitting on their front porch.”

During his few moments of leisure time, Riley practiced both the harmonica and guitar with assistance from his black friends and neighbors. Predictably, he began to cultivate a deep love and appreciation for the blues, often spending his Saturdays milling about the surrounding juke joints and honky tonks. As was typical in many impoverished communities of the time, Riley only attended three years of formal schooling. “It didn’t seem unusual – it was normal for us. We were sort of tied down in the South – there was poor people, and then there were us.”

In 1949, a fifteen-year-old Riley lied about his age in order to join the Army, where he served until 1953. Early in his deployment, Riley recorded three albums at a studio in Seattle, primarily covers of Hank Williams songs. While these were made for fun, Riley found the experience of recording to be exhilarating. Similar to his life back on the farm, Riley dedicated much of his free time in the Army honing his skills as a singer and guitarist, eventually finding success in the talent shows on base.

Following his honorable discharge, Riley returned home to Arkansas where he began a hillbilly band called the Arkansas Valley Ranch Boys. The band regularly appeared on the local radio station and performed at community functions. While Riley admits that his music at this time was unremarkable, elements of his signature sound were beginning to emerge. “Back then we just sounded like any regular hillbilly band. My singing was a little different. Even though I was doing country, I still had a little bit of blues sound in me, even back then,” he said.

Following his marriage and the birth of his first child, Riley relocated to Memphis to run a restaurant with his brother-in law. A fortuitous chance meeting would soon alter the trajectory of his life. On his way back to Memphis after a Christmas holiday in Arkansas, Riley picked up two hitchhikers by the names of Jack Clement and Slim Wallace. “We got to talking music and they told me they were building a studio over there, called Fernwood studios, and they had a band that played every weekend in Arkansas,” Riley recalled.

Clement and Wallace gave Riley an unexpected entrance into the music business, first as a member of their band and later as the first recording artist to record at Fernwood Studios. In the spring of 1956, Riley recorded his first two songs at Fernwood, “Trouble Bound” and “Think Before You Go.” While they didn’t attract much public attention, they did find their way into the hands of Sam Phillips at Sun Records, who promptly obtained the rights. Wanting a song that matched the rocking energy of “Trouble Bound,” Phillips insisted that Riley perform another. The result was the song “Rock with Me Baby,” which became the record’s B-side. His impressive work was rewarded with a record deal with Sun Records.

The late-1950s was an interesting and transformative time in America. Both the Cold War and the civil rights movement were in their early stages and rock & roll was experiencing a meteoric rise. Americans were also entering the so-called “space craze,” a period of time when the general public became enthralled with rockets, aliens, and the like. When Billy Lee Riley released his first hit “Flyin’ Saucers Rock & Roll” in 1957, just months before the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik I, he knew that he could capture the public’s imagination by combining two of their current obsessions.

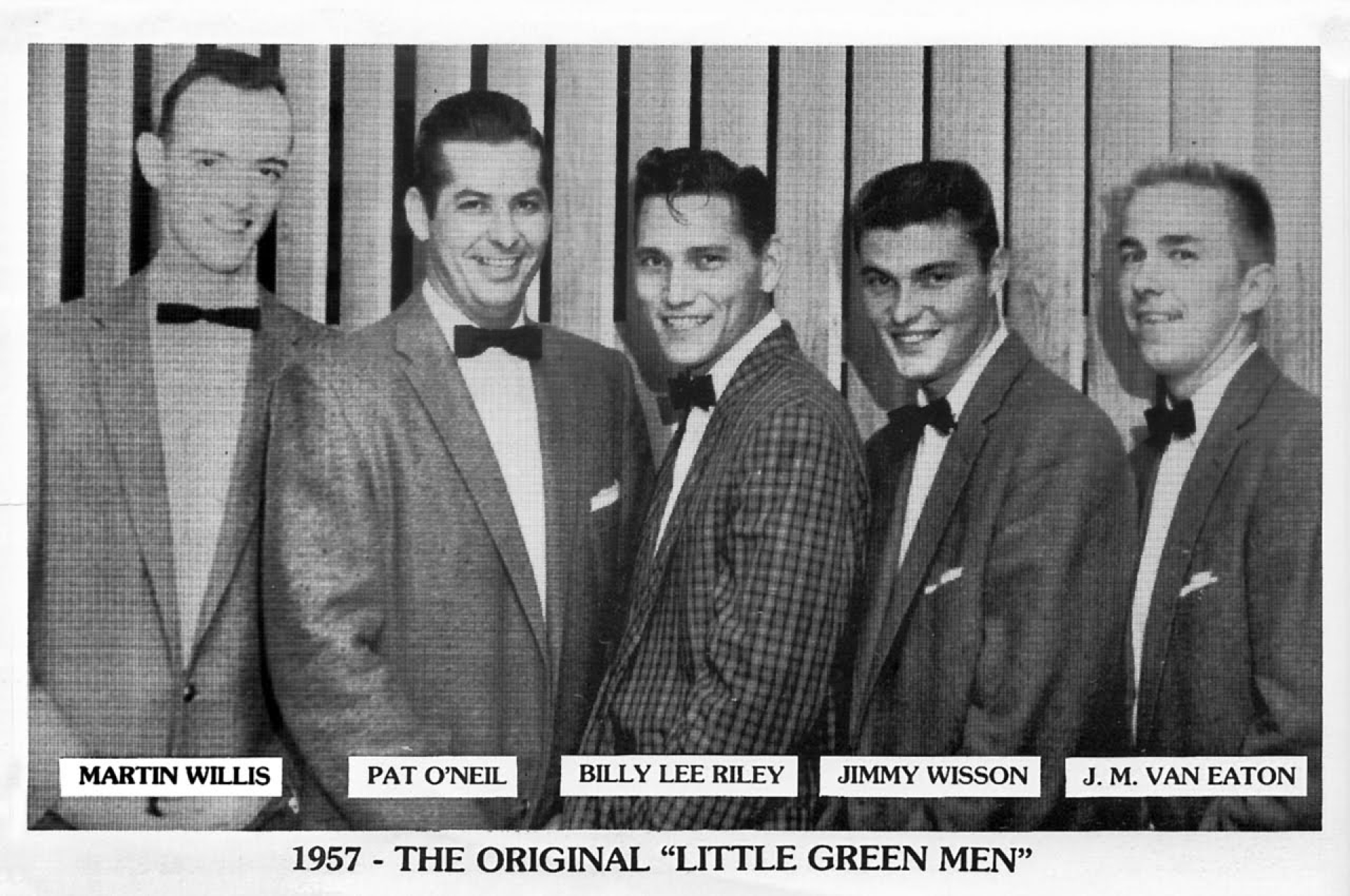

Backed by fellow iconoclast Jerry Lee Lewis on piano, Riley’s first single on Sun proved yet again that the boys at 706 Union Ave. were playing by their own rules. Years later, the cultural critic Greil Marcus would write “’Flyin’ Saucers Rock ‘n’ Roll’ was one of the weirdest of early rock ‘n’ roll records – and early rock ‘n’ roll records were weird!” In addition to giving Riley his first taste of success, the song also inspired Sam Phillips to name his band the Little Green Men. Aside from the multi-instrumentalist Riley, the group also included guitarist Roland Janes, drummer James Van Eaton, bassist Marvin Pepper, and pianist Jimmy Wilson, with Jerry Lee Lewis serving in a part-time role. The band eventually took on the role of Sun’s studio band, backing the likes of Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, and Johnny Cash. Asked to explain the band’s unique chemistry, Riley said “The only way I can say it is this: we were all just in tune with each other. It was a ‘feel’ thing and we just all felt the same thing. We didn’t go in there with anything planned, we’d just go in and start jammin’!”

Several months later, Riley and the Little Green Men released their second notable single, a scorching cover of Billy “The Kid” Emerson’s “Red Hot.” Featuring Riley at his growling, hollering best, the song seemed destined to be the big hit that had so far eluded him, but a confluence of events stopped it cold in its tracks. Despite the record’s promise, the track was ultimately abandoned by Sam Phillips, who chose to move his resources into promoting Jerry Lee Lewis’s “Great Balls of Fire” instead. Although Riley remained at Sun a while longer, the decision to shelve “Red Hot” did irreparable damage to his relationship with Phillips. “When he did that, I lost respect for him. That’s what caused me to leave Sun,” he said.

Although the era of the Little Green Men was short-lived, their recordings and live performances became the stuff of legend. From a fabled 72-hour performance at the Starlite Club in Frazier to a near riot-inducing show at Arkansas State University, the band is remembered decades later as being one of the most raw and raucous of their time. And regardless of their tepid sales, songs like “Red Hot” helped to inspire artists such as Bruce Springsteen and Bob Dylan, ultimately earning inclusion in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame’s list of “500 Songs That Shaped Rock ‘n’ Roll.”

Following his departure from Sun in 1960, Riley founded the Rita Record label with Roland Janes. While the label would prove to be short-lived, it did produce the national smash single “Mountain Of Love” by Harold Dorman. He later started two other labels, Nita and Mojo, where he would record under other names like Skip Wiley, Darren Lee, and Lightning Leon. Unfortunately, they also proved to be unviable. Frustrated by his recent series of setbacks, Riley relocated to Los Angeles in 1962. He began working as a studio musician for several high-profile artists, contributing guitar and harmonica work to such luminaries as Dean Martin, the Beach Boys, the Righteous Brothers, and Sammy Davis Jr. He also became a regular on the Whiskey A-Go-Go circuit, frequently traveling between New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. These engagements eventually resulted in the live album Whiskey a Go Go Presents Billy Lee Riley, released in 1965.

In 1970, Riley returned to Arkansas to begin his own construction business, putting his music career on the back burner. Like any true artist, though, he eventually returned to music in the late ‘70s, inspired in part by Robert Gordon and Link Wray’s covers of his classics “Red Hot” and “Flyin’ Saucers Rock and Roll.” In 1979, Riley held a triumphant return performance at Memphis’ Beale Street Music Festival, prompting a European tour throughout 1980 where he performed to adoring audiences.

In 1992, Riley returned with the album, reuniting with fellow Sun alumni Roland Janes, James Van Eaton, and Ace Cannon for his first all-blues album. “Blues is the best road I can be on right now. I can be accepted by blues people, because I’ve been considered half blues all my life,” he said at the time. Soon after, Riley’s profile was heightened even further when Bob Dylan invited him on stage during a concert in Little Rock, introducing him as “my hero.” “I sang ‘Red Hot’ and the people went crazy, man. They didn’t know I was supposed to be there and them people was climbing up on the chairs.” The following year, Riley served as Dylan’s opening act at several engagements.

In 1997, Riley returned to Sun Studios to record the album Hot Damn!, a masterpiece that was nominated for a Grammy. For the next decade, Riley continued to perform and record at an impressive clip until his death at the age of 75 in 2009. Six years after his passing, Bob Dylan offered this tribute to Riley:

Be the first to add your voice.