It was the “Summer of Love,” when psychedelic rock music was entering the mainstream and receiving commercial radio airplay and bands like the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane were emerging from the “hippie” subculture around San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district.

Two thousand miles away, during that same summer, Memphis was known more for the Southern soul music emanating from the halls of Stax Records and other labels, which was largely untouched by the influence of the West Coast.

Then came the Box Tops.

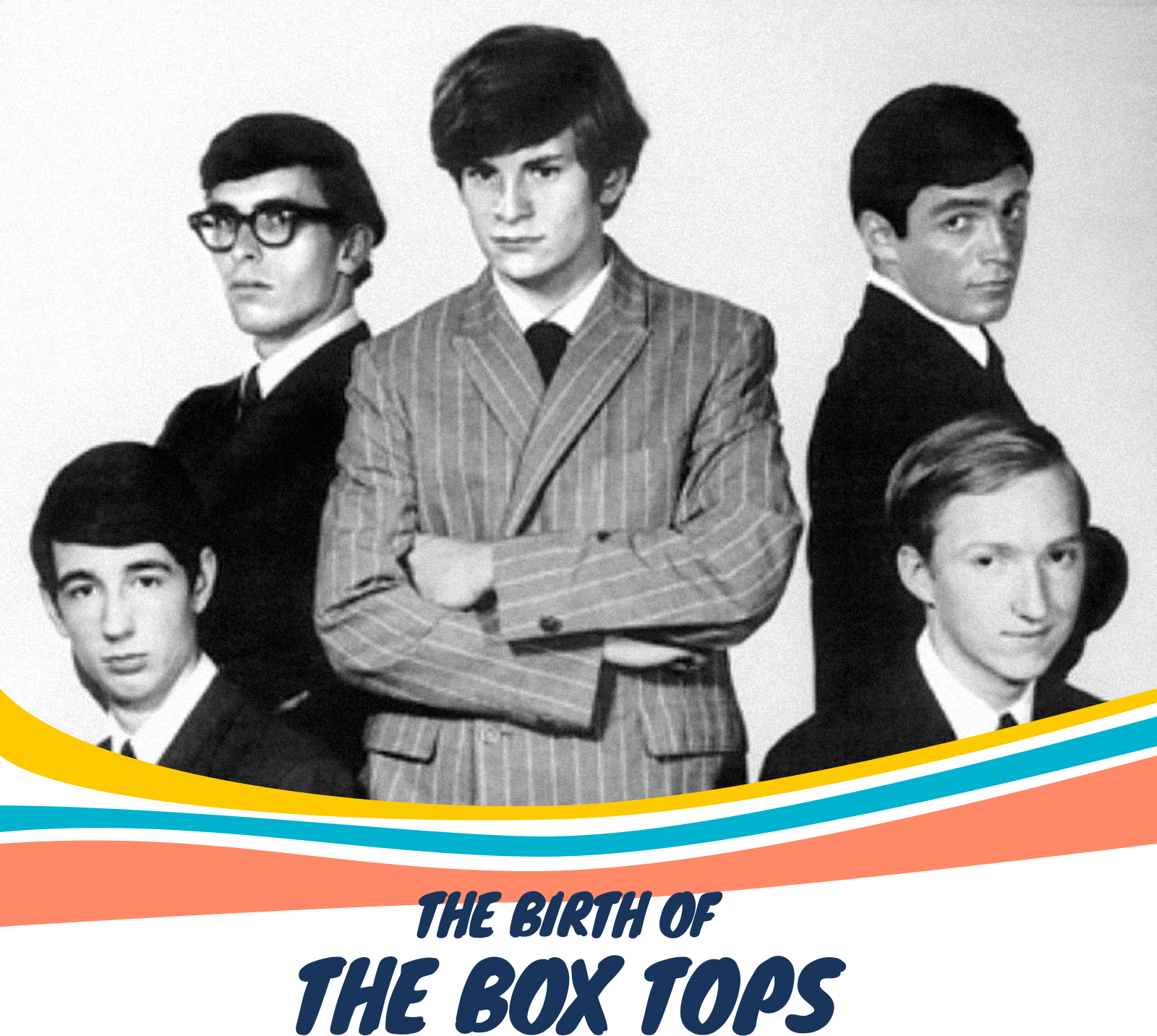

Composed of a group of youngsters steeped in both contemporary rock ‘n’ roll and soul, the group managed to marry these two worlds into an infectious blue-eyed soul, pop-oriented sound.

They emerged from a five-man band called Ronnie and the DeVilles, or simple the DeVilles (obviously named for a popular car of the time, as many bands were). Drummer Danny Smythe had joined several Bartlett High musicians to form the original iteration of the band, and through various adaptations and slight name changes, the DeVilles eventually added organist and guitar player John Evans, with vocalist Alex Chilton and guitarist and bassist Gary Talley and Bill Cunningham joining soon after. The newly constructed group soon found a following at the high school proms, sororities, and social clubs they frequently played. Though British Invasion bands like the Beatles, the Kinks and Them influenced their musical style, the principal influence came directly from Memphis soul and R&B and, to a lesser extent, from the blues and rockabilly sounds that emerged from Sam Phillip’s Sun Records. Many in the group also recognized the significant influence of eccentric Memphis deejay Dewey Phillips, who had helped to shape their eclectic musical tastes.

Lead singer Alex Chilton, who was only sixteen years old at the time, already possessed an enigmatic presence and forceful voice that quickly caught the attention of producer Dan Penn and songwriter Dewey “Spooner” Oldham, who helped secure a contract for the group with Mala Records. In 1967, their first effort in the studio produced a recording of a song written by Wayne Carson Thompson titled “The Letter.” Clocking in at just under two minutes, the song felt like an immediate hit and a perfect vehicle for Chilton’s prematurely gruff vocals. Unfortunately, just prior to their first nationwide record release, the group learned of the DeVilles popularity… not as a group, but as a group name. With two other groups recording under the same name, the band was forced to think of a quick name change. When one band member suggested that they have a contest where fans could send in 50 cents and a box top, producer Dan Penn then dubbed them the Box Tops.

By September, “The Letter” had raced up the Billboard charts to number one, where it stayed for an entire month, eventually selling over four million copies. Just months after working local frat parties, the Box Tops were soon on tour with the Beach Boys, performing in front of hundreds of adoring fans. “The Letter” went on to be awarded Cashbox Magazine’s Record of the Year, and received Grammy nominations for “Best Contemporary Group Performance” and “Best Performance by a Vocal Group.”

For their follow-up, the Box Tops returned to the songwriting of Thompson, as Penn produced their second release “Neon Rainbow,” which reached as high as #24 throughout a five week stay. Determined to strike while the iron was hot, the Box Tops would release three albums within a nine-month period during 1967 and ’68. By this time, Chilton and other members of the group had begun to rise to teen idol status, but friction was beginning to grow among members who suspected that Penn and Oldham might be more interested in Chilton as a solo artist. When the record company insisted upon using studio musicians to back Chilton’s vocals in the studio, it felt like their worst fears had been all but confirmed.

By early 1968, John Evans and Danny Smythe returned to school, and were replaced by bassist Rick Allen, a member of Memphis’ other white soul band, The Gentrys, and drummer Thomas Boggs, a member of Flash and The Board of Directors. Penn and Spooner wrote The Box Tops’ third single, which blended pop, soul, and country with a dose of psychedelia in the sound of the guitar. Chilton’s raspy vocal delivery on “Cry Like a Baby” helped to fuel the third single to number two on the Billboard Hot 100 charts, accompanied by sales of over two million records.

Following “Cry Like a Baby,” the band released a series of singles throughout 1968 and 1969, including “Choo Choo Train,” “I Met Her in Church,” “I Shall Be Released,” and “Soul Deep,” each of which hit the Billboard Hot 100 charts, but with “Soul Deep” (another Wayne Carson Thompson composition) being the only one to crack the Top 20. By the end of 1968, the band switched producers, tapping the team of Tommy Cogbill and Chips Moman of American Sound Studios. Under this new team, the band released the tracks “Sweet Cream Ladies, Forward March” and “Turn On A Dream,” among others.

In August of 1969, Bill Cunningham left The Box Tops to return to school. He was replaced by Harold Cloud on bass. By December of that same year, frustrations with the music industry, including disrespect by promoters and fleecing by lawyers and managers, began to wear on the young musicians. During one particular stop in London, England, the band cancelled the tour after the local promoter ignored the band’s rider agreement, insisting that they play the tour with the opening reggae act’s toy drums, public address system amplifiers, and a keyboard with broken speakers. Within months, the remaining founding members of Talley and Chilton were ready to move on and disbanded the group, even though the record company released a few previously recorded singles under the Box Tops name, like 1970’s “You Keep Tightening Up On Me” and 1971’s “King’s Highway.”

Post-Box Tops, each of the original members continued with projects within the music industry. Alex Chilton hooked up with former high school friend Chris Bell, and power pop icons Big Star soon emerged. Gary Talley worked as a session guitarist with artists and producers like Billy Preston, Billy Lee Riley, Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and others. Bill Cunningham completed a master’s degree in music and chose a classical music career path, later performing in the White House orchestra alongside some of the world’s best performers. John Evans continued playing with groups in Memphis, working as a guitar luthier before switching to a career as a computer network administrator. Danny Smythe also continued to perform in Memphis with soul and blues groups, but added a career in art and advertising.

In 1996, Cunningham organized a reunion of all of the band’s original members. Subsequently, they released a self-produced album of new material, Tear Off!, recorded at Memphis’ Easley McCain Recording. The album included a new original by Gary Talley, as well as covers of Bobby Womack, Eddie Floyd, and The Gentrys. The album also featured The Memphis Horns. Busy schedules and other careers only allowed for occasional reunion performances, and the Box Tops performed their last Memphis concert on May 29, 2009, at The Memphis Italian Festival.

In these trivia-obsessed times, it is worth noting that the very first number-one hit record made in Memphis by a Memphis act was, in fact, “The Letter.” Despite their relatively short existence as a band, the Box Tops managed to leave an enduring legacy of blue-eyed soul, AM pop, early funk, and Beatles-esque wordplay. It has been said that no American group since the Righteous Brothers had looked whiter, yet sung blacker. Even though The Box Tops were only together for about three years, it was long enough to deliver two classic hits, a legendary front man, and one of the most remarkable journeys in Memphis music history.

Be the first to add your voice.