From a mail boy at a radio jingles studio to one of popular music’s most celebrated producers and engineers, Jim Gaines’ life story reads like an Horatio Alger tale: an adventure that extols the virtues of hard work and determination. Anyone who knows the 7-time Grammy winner will tell you, Jim Gaines has earned his reputation as one of the most humble and generous men in a notoriously ruthless industry. These attributes served him well through five decades in the music business, where he has left an indelible mark on the music of artists such as Huey Lewis and the News, Carlos Santana, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Steve Miller and countless others.

Jim Gaines was born on October 2, 1941, in the small town of Parkin, Arkansas, before relocating 30 miles southeast to Memphis in the early 1950s. Following his high school graduation, Gaines began working at Pepper Tanner, one of the world’s largest producers of commercial jingles. After a year of working as a “gofer,” where he largely helped around the mailroom, Gaines approached the chief engineer and offered to take over the role of making tape copies. “I created a role in the company for myself that hadn’t existed, and that was my start,” he remembered. For the next eight years, Gaines continued to climb the ladder within the company, moving from mixing, to tracking, to eventually supervising several satellite studios around the region.

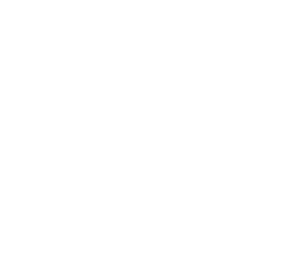

During this time, he met Steve Cropper and Booker T. Jones, who were assisting with tracking. “One day I get this call from Cropper saying ‘Would you be interested in helping us over at Stax sometime?’ Of course I said yes.” In 1968, Gaines began a brief but vigorous apprenticeship under Cropper, working at Stax several nights a week following his shifts at Pepper Tanner. “I would see artists like Sam and Dave come in and work with the writers, folks like David Porter and Isaac Hayes, and we would put down the rough tracks so that we could remember what we did later,” he said. Although his time at Stax was short-lived, Gaines credits the experience with teaching him some important lessons that would serve him well in the coming years.

In 1970, Steve Cropper left Stax in order to open the Trans-Maximus (TMI) recording studio and brought Gaines into the fold. For the next two years, he served as TMI’s chief engineer, before being recruited to San Francisco by studio owner Wally Heider. “When I first arrived in San Fran, they told me that they were going to give me a song to mix over the next hour or so and that we’d see what happened. It happened to be a song from Creedence Clearwater, my favorite band. After they listened to my mix, they said ‘How soon can you be here?’” Gaines accepted the job and relocated to San Francisco in the early 1970s, where he would primarily remain for the next two decades.

After arriving in California, Gaines immediately began working with a slew of acts from varying genres. “San Francisco is a very multi-dimensional music scene, and within six months I was the resident expert in cutting Dixieland jazz and belly dancing records,” he said with a laugh. Before long, he began working with more high-profile acts such as Tower of Power and Van Morrison as a recording and mixing engineer, but his demanding schedule soon became overwhelming.

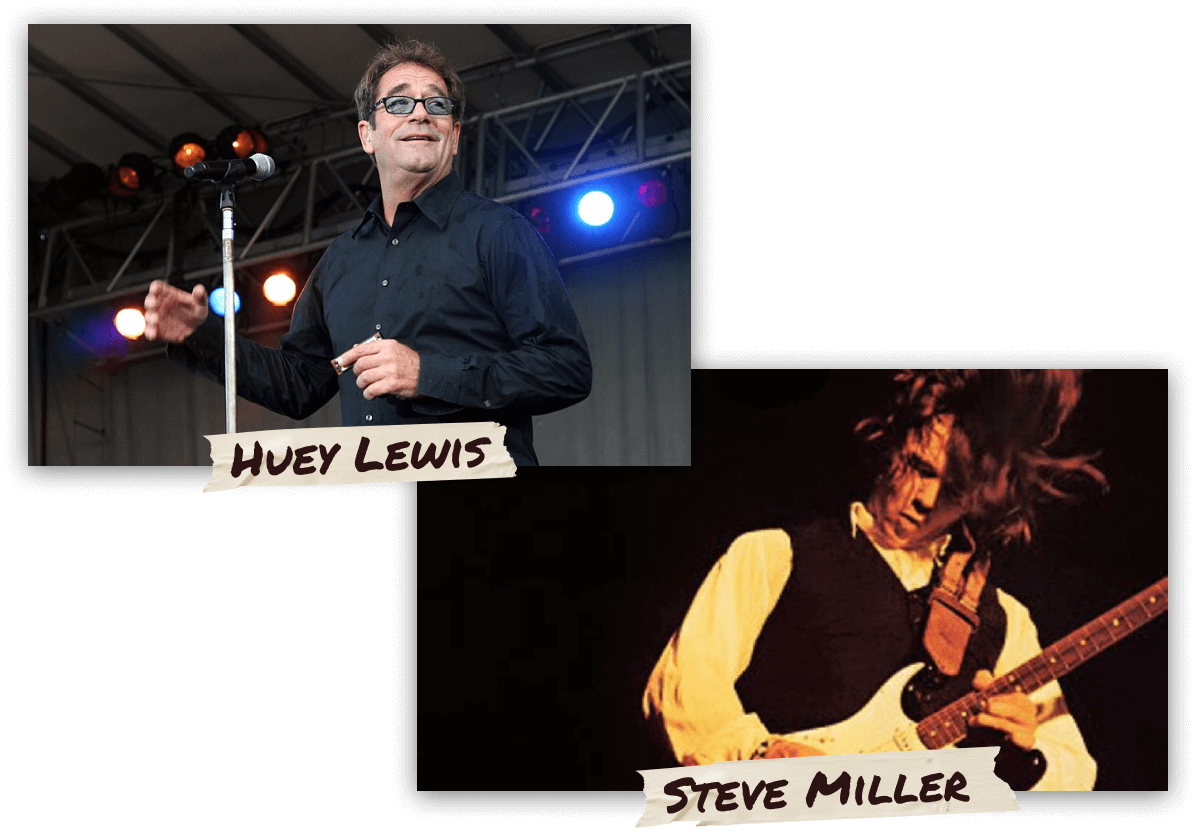

“I was working so many hours that my wife at the time threatened to move back to Tennessee without me,” he explained. Fortunately, the owners of a new Seattle-based studio called Kaye-Smith reached out and offered Gaines a less strenuous position. “Although we were never able to break open the Northwest, I was able to work with Dionne Warwick, Bachman Turner Overdrive, and the Steve Miller Band there.”

He had already produced hit songs, but Gaines’ first massive record came in 1976 with the Steve Miller Band’s album Fly Like an Eagle, featuring the anthem of the same name. “That was a special, special project to me, because Steve would let me experiment and try out-of-the-norm techniques, like cutting vocals in the control room right beside me, or cutting guitars with a Fender Princeton amp, at my feet, under the console. I was allowed to do those things,” he said. The next year, Gaines was also a key figure in Miller’s successful follow-up Book of Dreams, which produced three more hit singles.

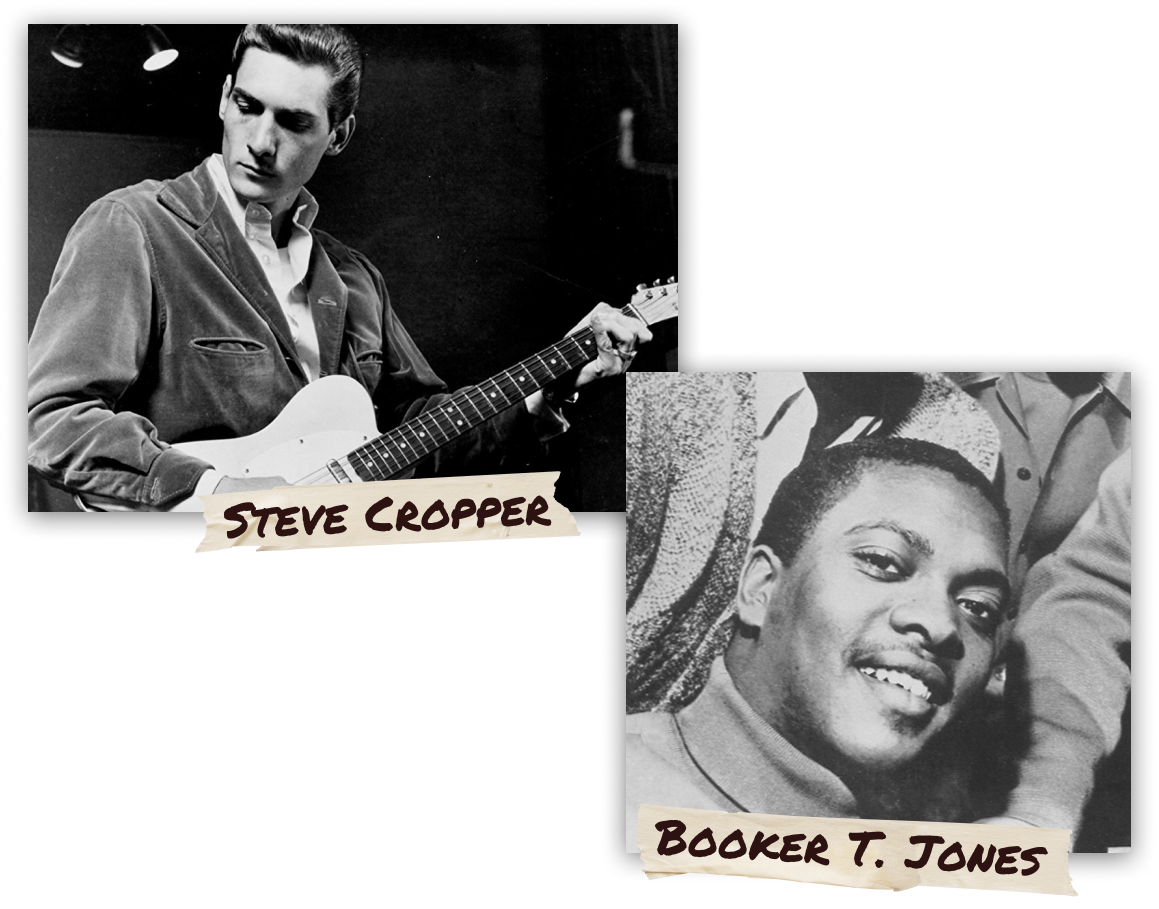

Despite these successes, Gaines’ relationship with the studio slowly began to sour. “Within a six month period, I cut demos for Huey Lewis, Tommy Tutone, and Pablo Cruise. Each time, I was promised a job, and all three times they went to L.A.” Understandably frustrated, Gaines decided to leave the music industry altogether, relocating his family to Oregon and pursuing other careers for the next two years. However, a fateful phone call would change the trajectory of his life yet again.

“One day Huey [Lewis] called me and said ‘Look man, you’ve got to come back and work with us. You’re the only guy who understands our sound.’” Although initially reluctant, Gaines ultimately capitulated and traveled to San Francisco for a session. The result was the group’s first top-ten hit, “Do You Believe in Love,” which gained heavy rotation on both radio and MTV. “Once people learned that I was back in San Francisco, my phone was ringing off the wall. It was non-stop after that,” Gaines recalled. “If you’re a successful engineer, eventually someone is going to want you to produce them. That’s just how it goes.”

As the offers came rolling in, Gaines quickly became one of the country’s most in-demand engineers, regularly working with some of music’ biggest names throughout the 1980s. Somewhat poetically, his most notable collaborator became the man who had convinced him to return to music in the first place: Huey Lewis.

Gaine’s history with R&B music made him a natural fit for the band, which was looking to infuse their rock sound with more soulful elements. “The whole idea of Huey Lewis and the News was to mix an R&B feel with fun rock ‘n’ roll, and that’s what we went for,” said Gaines. For the better part of the decade, Gaines worked with Huey Lewis as a co-producer, resulting in thirteen Top 40 hits and a string of era-defining albums.

“All I can say is this: when we did those first records, especially the first two (Picture This and Sports), we were creating a new sound. I didn’t go with it in the front of my mind saying, ‘I’m going to this session to create a sound,’ but once I’d get into the session, and I’d hear those songs coming up, then I’d start to say, ‘We need to do this to make that work,’” Gaines recalled. “When we were doing those records, I wanted to create some fun, good-time songs. All of us did. That’s the way the band was, and we were all in sync at that point in time. That’s why they brought me out of retirement; because they felt like I understood what they were trying to go for.”

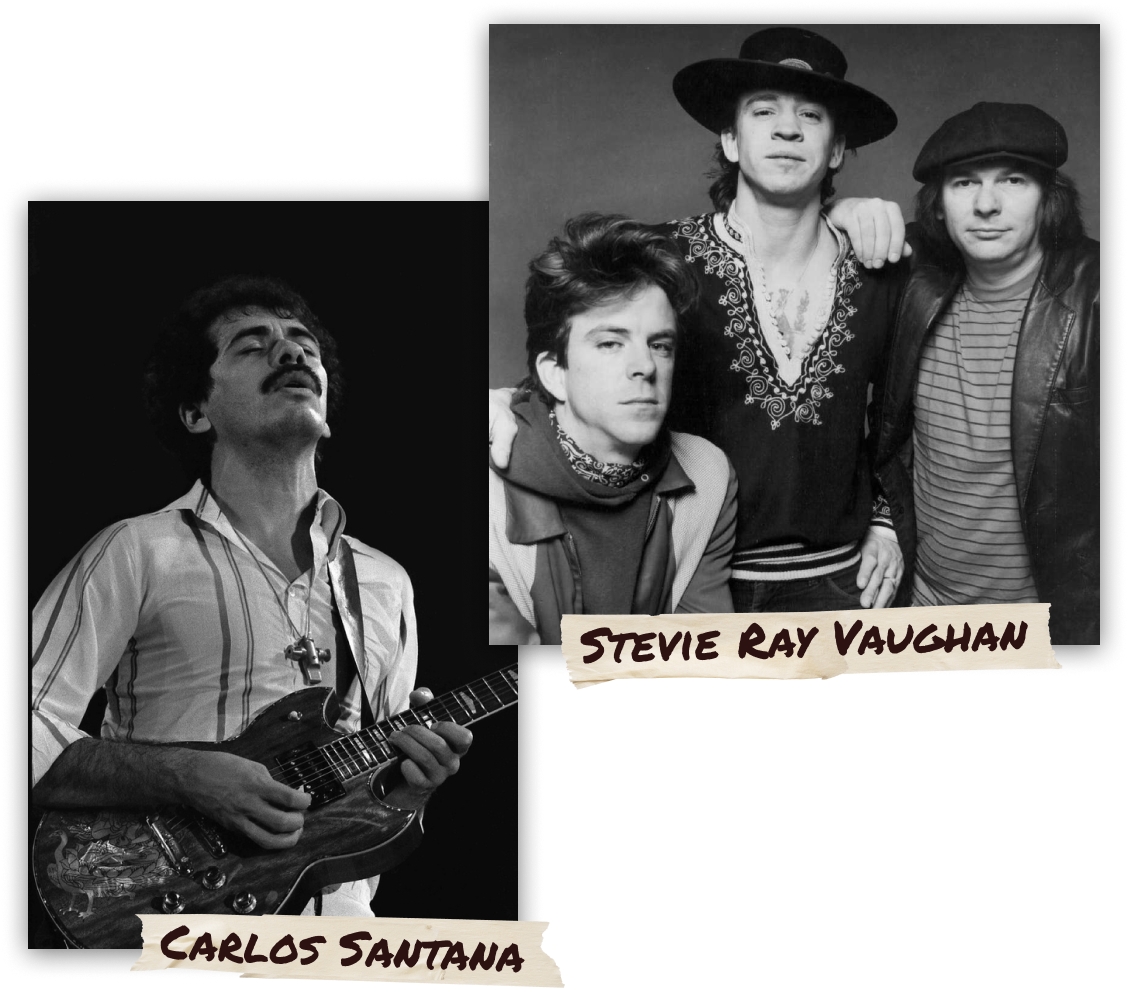

Just like that, the coveted “Jim Gaines Sound” was born, heightening his profile and allowing him more opportunities to sit in the producer’s chair. At the heart of Gaines’ sonic philosophy was a desire to replicate the sound and energy of a live performance as much as possible. “I used to go and see the artists live first, before recording,” he said. “When I’m in the studio working, I’m trying to capture the energy and liveliness of those performances on the records. I kind of became known for that punchy, live feel as my signature.” In addition to his work with Huey Lewis, the “Jim Gaines Sound” is also apparent on seminal ‘80s albums from artists such as Carlos Santana, Bruce Hornsby, the Neville Brothers, and more.

As the decade came to an end, Gaines was given the opportunity to work with one of blues music’s greatest stars, who helped to set his career on a new path. In 1989, Texas guitar wizard Stevie Ray Vaughan utilized Gaines’ producing, mixing, and engineering skills for his renowned album In Step. When Vaughan requested to have ten amplifiers recorded at once, Gaines knew he would need more space than his small New York studio would allow. Gaines decided to take the proceedings back home to Memphis, where he set up shop in Kiva Studios. Soon after wrapping the session, Gaines would move home to the Bluff City for the first time in two decades, where he remains to this day.

Not only did his work on In Step bring Gaines home, it also opened an unexpected floodgate into a new market. “Once we had a top 20 single, the blues people went ballistic. I think the appeal was that I didn’t do straight blues, I did rockin’ blues. The blues community just decided ‘This is the new guy.’ And I’ve had a lot of success with that,” he said.

One of these success stories came about almost immediately, when Gaines worked with icon John Lee Hooker for his Grammy-winning comeback album The Healer. “We loved John Lee, he was just the sweetest man. To have that success for him just made our hearts feel good,” said Gaines. Since that point on, Gaines’ work has largely focused on blues music, sending him on various journeys to lend his skills to artists around the world.

A decade after his collaborations with Vaughan and Hooker, Gaines briefly departed from his blues-focused work in order to assist an old friend and frequent collaborator on a new album. Yet despite the quality of their previous music created together, nobody could have predicted the success of Carlos Santana’s Supernatural, which went on to reach No. 1 in eleven countries and break the record for the most Grammy wins for a single album with nine.

Today, Jim Gaines continues to work tirelessly as a producer and engineer, but has also found time to work on his forthcoming autobiography, Thirty Years Behind the Glass : From Otis Redding and Stax Records to Santana’s Supernatural. Written with help from author Lee Zimmerman, Gaines says that he has been working on the book for the past few years.

Be the first to add your voice.