Fred Ford, Jr. was born on Valentine’s Day, 1930 to Fred and Nancy Taylor Ford. When he was just two his parents separated and he and his sister were raised by their mother and grandmother in the area north of Memphis known as the Douglass community.

His earliest musical recollections were of his mother singing around the house and in church. Mama Ford, it seemed, had a beautiful voice. “That’s how my mother impressed me. When she would sing she had that look, like if she was singing at church she wouldn’t leave a dry eye.”

Ford set out on his musical path when his grandmother bought him a clarinet, but he fell in love with the sound of the trumpet after hearing Glenn Miller’s In the Mood. He joined his high school’s legendary jazz band the Douglass Swingsters, led by their principal L.C. Sharpe.

In 1945, at the age of 15, Ford had his first professional job playing in the Elks Lodge on Beale Street in Andrew Chaplin’s band, backing Dwight “Gatemouth” Moore. Mr. Chaplin was an older musician who had been a drummer with the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra and taught young Ford the ins and outs of the music business.

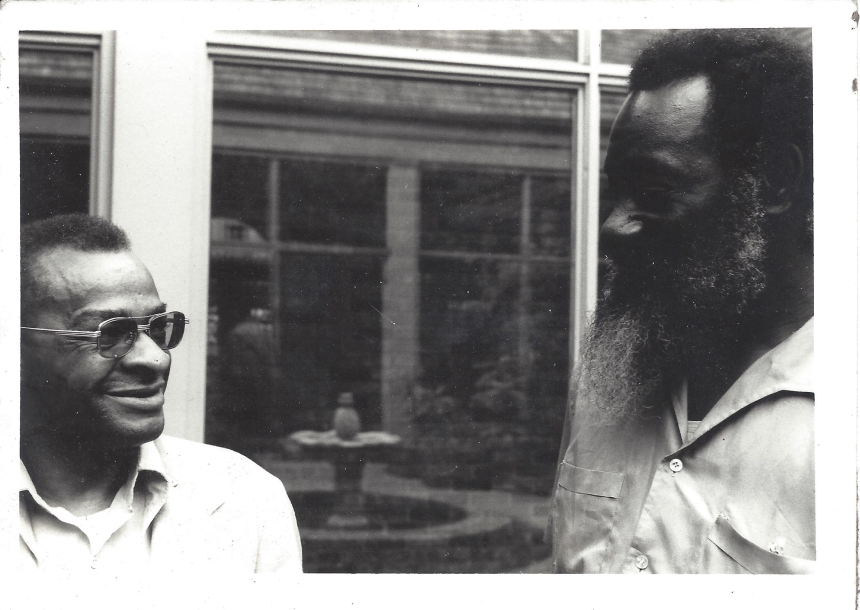

That same year Ford met Phineas Newborn, Jr., who would become a lifelong friend. Newborn, known by many in Memphis simply as Junior, was a prodigy pianist who later exploded onto the New York jazz scene in the 1950s. He came from a musical family that included his father, a drummer, and younger brother Calvin who excelled at guitar.

“When I first met Phineas, he was 13 and I was 15,” said Ford. “I actually thought that Phineas was a midget as a little boy, because there was no way in the world a little boy was supposed to play that much music. I told him about that and he laughed. I had put a Coca-Cola case on the piano seat for him to be able to have on the piano.”

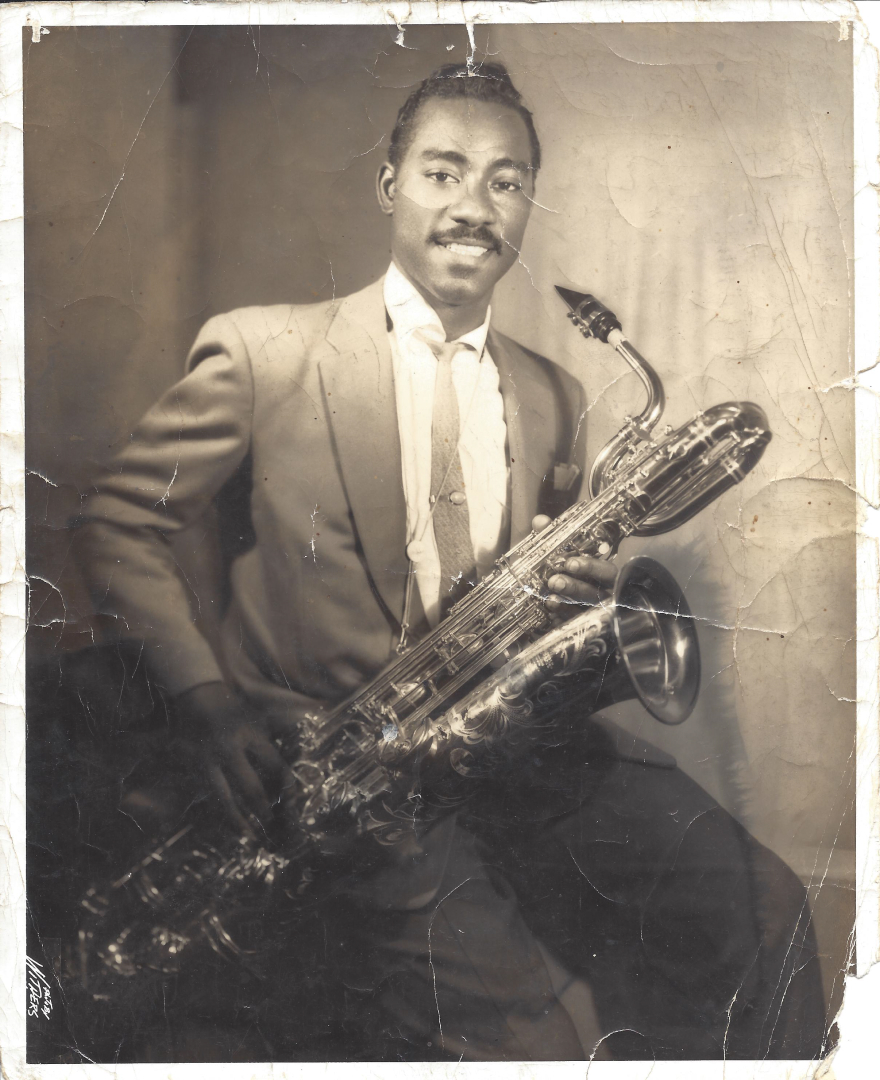

The next year, Fred Ford was playing in the band of Onzie Horne, Sr., and discovered the baritone saxophone. “We had six reeds; three tenors, two altos, and a baritone, five trumpets and four trombones,” recalled Ford. “Now I’m playing trumpet in the trumpet section. Finally, the guy playing baritone couldn’t read the music fast enough. The orchestra had an overabundance of trumpet players. I said, ‘I don’t want to play no saxophone, but if I play a saxophone the only one I would play would be the baritone.’ Onzie said, ‘Well, that’s what you’re going to have to play.’ Well, I’m a team player, plus, I already had the instrument. That’s when I put down the trumpet and started playing baritone saxophone. I never picked the trumpet up again.”

There is a tradition in Memphis of teenagers playing music with grown men. An early example was 15-year-old Thomas Pinkston playing violin in W. C. Handy’s Memphis Band in the 1910s. In some cases, it was a family situation like with the Steinberg, Jackson or Newborn families. Sometimes economic reality was at play as high school-aged kids did not demand as much pay as experienced musicians and, surrounded by more experienced players, their gaffes were less noticeable. The Bar-Kays’ James Alexander, legendary drummer Howard Grimes and many others played clubs with grown men when they were as young as 13.

Fred Ford was the beneficiary of this tradition.

Two men Ford met in 1946 became his mentors and shaped his musical direction. Apart from Onzie Horne, Sr. who was an arranger, band leader and keyboardist, there was Bill Harvey, a saxophonist and bandleader at the legendary Club Handy. He said of their influence: “Onzie Horne and Bill Harvey shaped us, theoretically, you know, and how to play.”

Ford’s generation of Memphis musicians learned to play in the high schools, in the clubs, at gigs and after-hours jam sessions. They played constantly, always pushing themselves and each other, and became world class artists. In the 1940s and ‘50s, these hard-working players often met after gigs on Beale Street at Andrew “Sunbeam” Mitchell’s Club Handy. Bill Harvey led the band, and the jam sessions included future stars such as George Coleman, Harold Mabern, Charles Lloyd, Phineas Newborn and Willie Mitchell, as well as lesser-known musicians like Oscar Armstrong, Emerson Able, Leonard “Doughbelly” Campbell. They would often be joined by members of the Count Basie Orchestra, Duke Ellington Band and other touring groups.

Jazz was played exclusively at the Club Handy but the ironic truth about this original American music is that it was only truly embraced in a handful of U.S. cities and more widely in Europe. Many Memphis jazz musicians left home for New York, Los Angeles or overseas simply to earn a living playing the music they loved. It’s a sad fact that most of them are more renowned outside of their hometown as is often the case. As Jesus says in Luke 4:24, “But I tell you the truth, no prophet is accepted in his own hometown.”

Ford’s philosophy was simple.

Between 1946-1952, Ford spent most of his time while in Memphis, playing in Onzie Horne’s band. In 1949, he began touring with the Bill Harvey band on the Royal American Big Band Top Show, traveling through Florida, Texas and as far north as Canada. In Houston they met Don Robey, an African American entrepreneur who owned the record company Duke/Peacock.

In 1950, the Bill Harvey band with Fred Ford became the house band for Duke/Peacock and toured supporting Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown. They served the same role for Johnny Otis, including on his recording of Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog.” Famously, Ford and the horn section howled like dogs at the end of the record.

Ford entered the service in 1952 and was posted in Korea, where he played in Army bands. Upon his discharge, he returned to Memphis and worked with Bill Harvey, B.B. King and was active in the local jazz scene. He also recorded at Sam Phillips’ Sun studio behind Charlie Rich and Jerry Lee Lewis.

As an in-demand baritone saxophonist, Fred Ford recorded at the top Memphis studios in the 1960s and ‘70s with an impressive list of talent including Dionne Warwick, Alex Chilton, Rufus Thomas, Aretha Franklin, B.J. Thomas, Wilson Pickett and many others.

His old friend Phineas Newborn, Jr.’s career had a series of bumps and turns that landed him back in Memphis in the 1970s after a spectacular launch in New York two decades previous. Atlantic Records partner Jerry Wexler agreed to fund a record by Phineas that was produced by Ford. Here is Phineas was issued in 1956, Newborn’s first national release also on Atlantic Records. Phineas received a Grammy nomination in 1975 for his album Solo Piano, produced by Fred Ford.

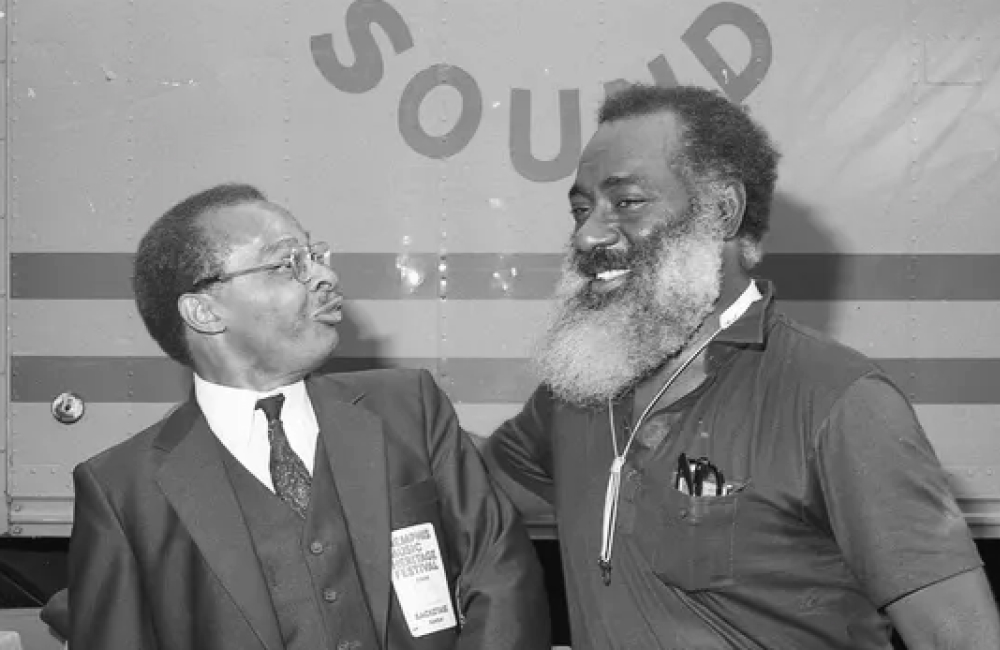

In the mid-1970s a new organization was formed by local businessmen with a social and economic development goal. Through Memphis in May they hoped to tap into various elements of local cultural touchstones by presenting events centered on broad topics: music, art, barbecue and sunsets over the Mississippi River.

The Memphis in May progenitors had no real expertise in indigenous music, so they turned to Irvin Salky, an eccentric attorney who represented Phineas Newborn, Jr., and was known to have connections with black musicians. Salky enlisted Fred Ford to help the effort while he served as gatekeeper between Ford and the Memphis in May committee.

Using his personal relations, Ford booked friends and colleagues for the 1977 and 1978 Beale Street Music Festivals. It was his vision to include jazz, blues, gospel, rock and rockabilly on the same stage, a format that continued for several years. In essence, he was the unacknowledged founder of the Beale Street Music Festival.

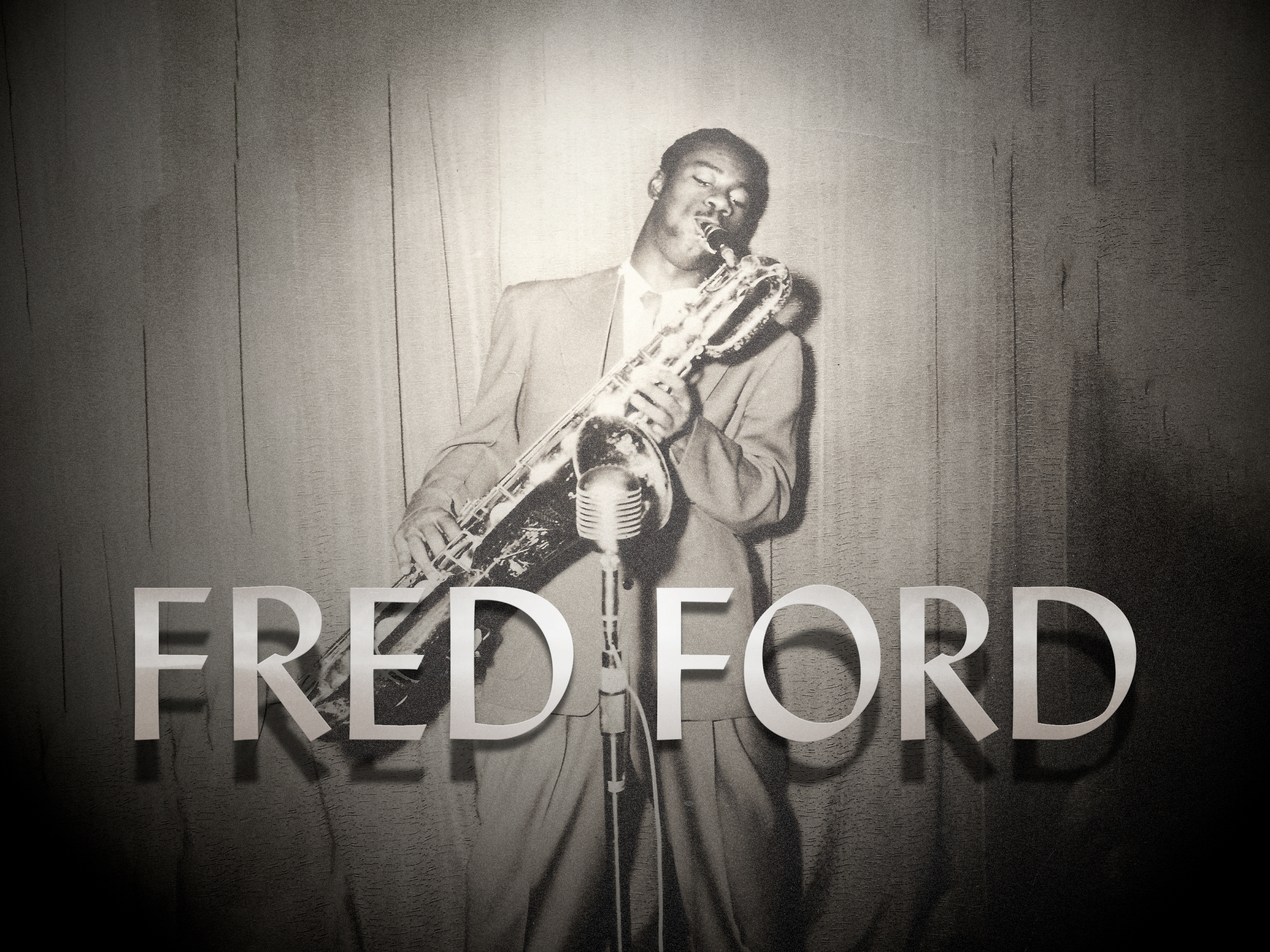

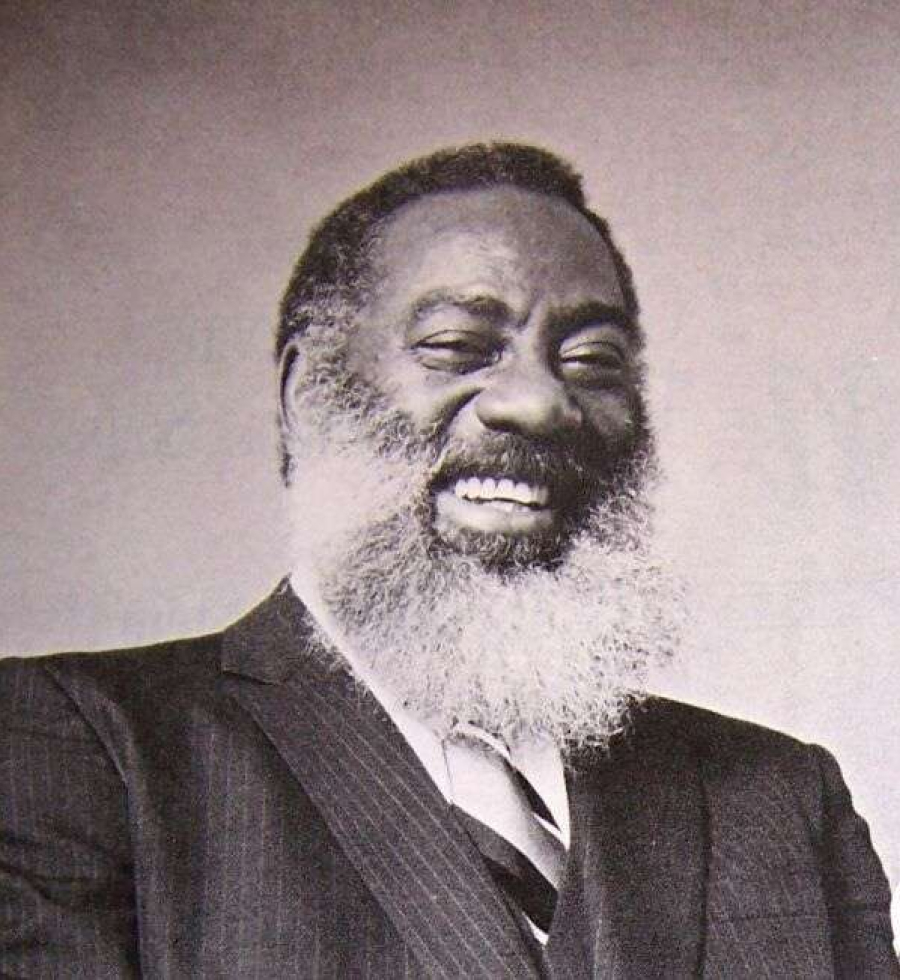

Ford was a gentle soul inside of an imposing physical frame. He had an on-stage alter ego that emerged when he played saxophone calling himself Sweet Daddy Good Low, who would smile and dance joyfully as others soloed.

In the 1980s and 1990s he played in a trio with his friends Robert “Honeymoon” Garner, the B3 organist, and drummer Bill Tyus. They worked a regular gig at the Peabody Hotel from 1985 to 1988, and continued to work around Memphis and occasionally out of town until 1999.

Charlie Rich hosted jam sessions in his home studio on Tuesday evenings with Ford for a number of years. Those recordings were never released. In a 1985 New York Times article, Ford was dubbed “Memphis’ best kept secret.”

Ford was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1999 and a benefit was held to raise money to pay his medical bills. Alex Chilton, Rufus and Carla Thomas, The Hi Rhythm Section, Lucero and other top Memphis artists donated their talents to the event. Fred Ford died November 26, 1999.

* many quotes are from Smithsonian Institution interviews conducted on May 20, 1992 by David Less, Pete Daniel and Charlie McGovern. Additional quotes from 1991 interview with David Less. Copyright 2022 David A. Less. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Be the first to add your voice.