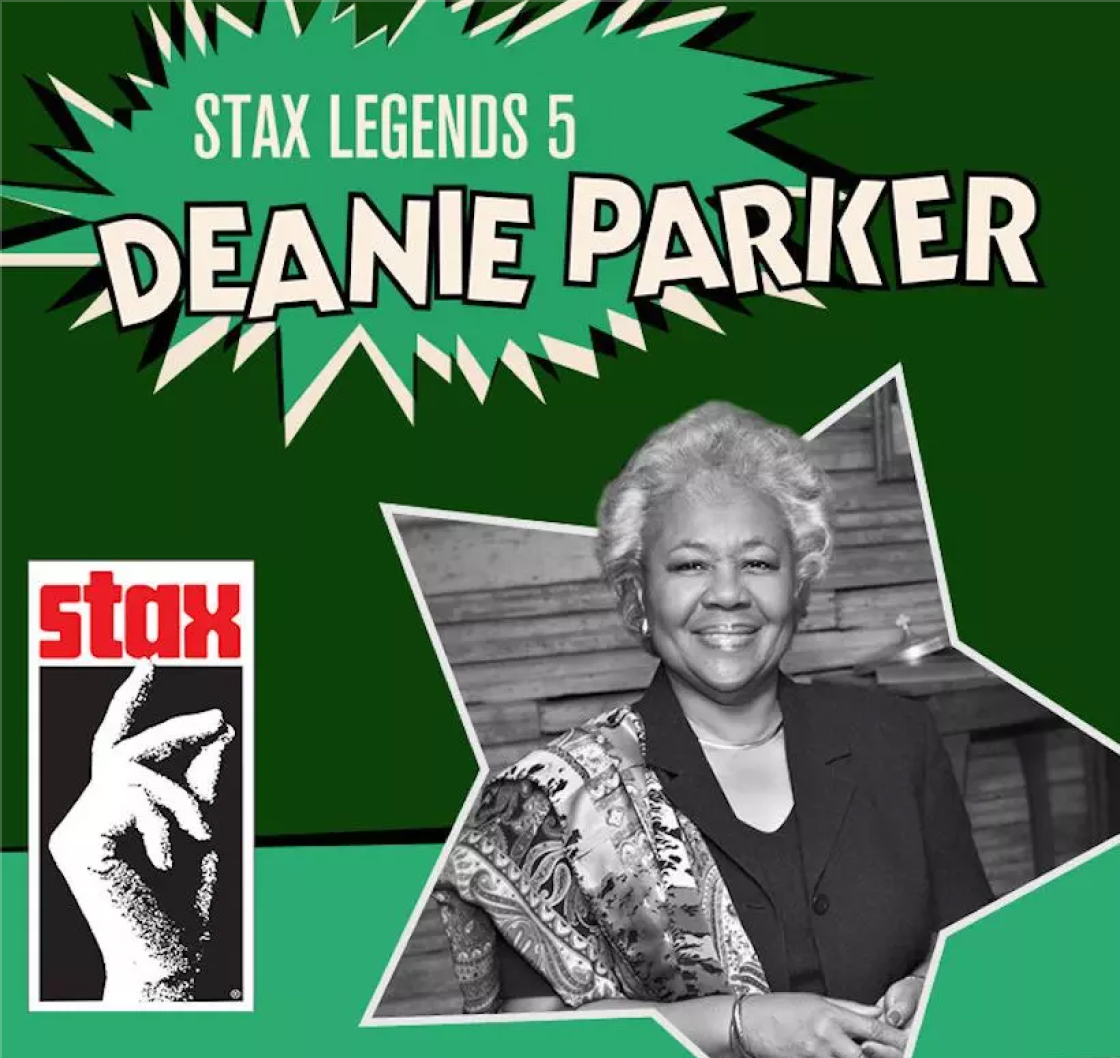

Deanie Parker was born south of the Crossroads to The Blues on her grandparents’ farm in rural Duncan, Mississippi.

The first music she ever heard was Negro spirituals, gospel songs, and Wesleyan hymns sung a cappella at an African Methodist Episcopal church built by her family in Duncan, Mississippi on a gravel road across from a bayou.

Hoopers’ Chapel AME Church has now been reconstructed inside the Stax Museum of American Soul Music and a plaque with a similar message is located at the original site of the church.

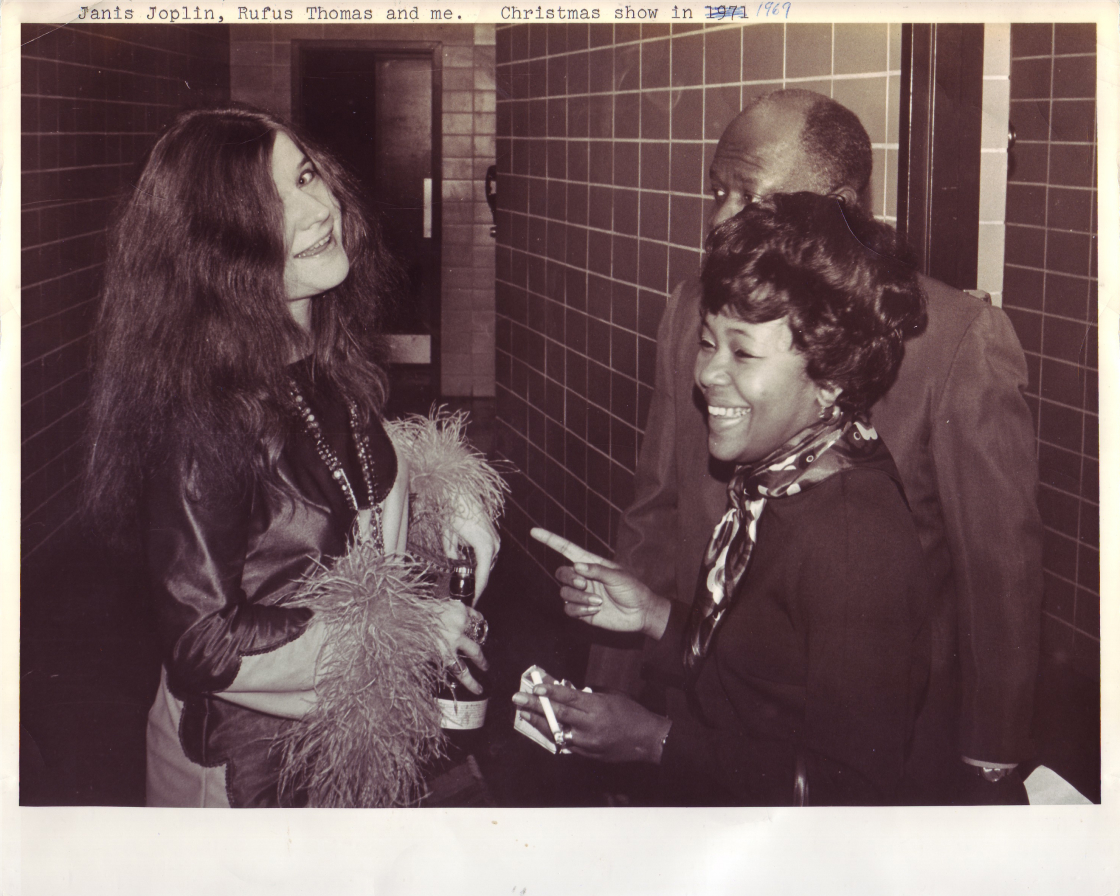

Even after Deanie moved up north to attend school, she spent her summers in the Mississippi Delta. The family radio stayed tuned to WDIA-1070 all day, every day, until the AM station signed off at sunset. The station was hosted by now-legendary DJs like Nat D. Williams and Rufus Thomas, both Memphis Music Hall of Fame inductees. But the music never stopped – gospel, spirituals, big band jazz and the Memphis Blues. Her grandmother always had records on the old Victrola and Deanie listened and dreamed. A broomstick was sometimes her microphone.

The year was 1952. Eisenhower was president and television was black and white. Deanie Parker’s world changed and got a lot bigger and more diverse when she was replanted in Ironton, Ohio.

Her first-grade classmates were mostly white and so were many of her playmates. All her teachers were Caucasian, female and unmarried. And so was her piano instructor. She would sometimes be whacked on the hands for playing B.B. King, Chuck Jackson and other popular musicians.

Deanie enjoyed singing in the church choir, the Glee Club, her piano recitals and learning to play music by ear. And the dominant music genre to which she listened that was broadcasted in the hills of Ohio, on the edge of Kentucky and throughout the mountains of West Virginia was different — with a titillating twang.

In her sophomore year at Ironton High School, Deanie’s mom gave her a shiny new transistor radio on which she heard a station broadcasting in Nashville, TN. The radio station’s signal could only be picked up at bedtime. It was WLAC radio and Hoss Allen was playing “These Arms of Mine.” It was Otis Redding. The song touched her heart and turned her head and she never looked back. This was rhythm and blues — the new Memphis Sound — created at Stax Records and made in Memphis, Soulsville, USA.

Deanie moved to Memphis in 1961. While attending Hamilton High School, Deanie formed a group called the Valadors, and she re-embraced that soulful musical sound she’d grown up with. The Valadors entered a talent contest at the Old Daisy Theatre on Beale Street. The group won, claiming the first prize, an audition for Jim Stewart, the founder of Stax Records.

Deanie’s dream was to become a singer and recording artist. But they had to have an original song to make a record, so she wrote “My Imaginary Guy.” Stax released it in 1963 and it gained some regional success. Deanie Parker’s career in the music business was underway.

However, Deanie never craved the road travel, and — of course — resented the segregated, inferior treatment Black entertainers had to endure. She worked most of her senior year at Hamilton working at the Satellite Record Shop. While there, she and Stax Record’s part owner, Estelle Axton (Jim Stewart’s sister), teamed up to create The Mad Lads’ first hit entitled “I Want Someone.” And while she wrote more songs for other Stax artists, she also wrote and recorded songs for herself, among them “Each Step I Take” (with Steve Cropper) and “Mary Lee Can You Do the Bumble Bee.” After graduation she spent a year working as a DJ for Memphis’ iconic WLOK radio station before returning to Stax, where in 1964, she convinced Jim Stewart to let her try her talents as the label’s first publicist.

Jim Stewart offered Deanie a career at Stax as the company’s publicist and Al Bell contracted Motown PR man Al Abrams to mentor her, making her one of the first female publicists in the music business. Initially one of only two office employees, Parker learned on the job while continuing to write for such artists as Carla Thomas, Albert King and the Staple Singers. She successfully marketed such Stax musical icons as Sam & Dave, Johnnie Taylor, Little Milton, Isaac Hayes, Wendy Rene’, David Porter, Richard Pryor, Billy Eckstine, Moms Mabley, Luther Ingram, Jimmy Hughes, The Dramatics, Rev. Jesse Jackson, Rance Allen, Judy Clay, The Emotions, Rufus and Carla Thomas, The Soul Children, The Bar-Kays, Mel & Tim, Linda Lyndell, Jean Knight and others.

She also wrote liner notes, documented recording schedules in the studios, and served as photographer and press correspondent.

Deanie Parker also continued to write songs every chance she got, including “No Time to Lose” for Carla Thomas, “Sleep Good Tonight” for Sam & Dave, “Don’t Mess with Cupid” for Otis Redding, “Who Took the Mary Out of Christmas” for the Staple Singers, “Love is You” for Eddie Floyd, “Ain’t That a Lot of Love” with Homer Banks for 3 Dog Night, Taj Mahal and Simply Red. And she wrote songs for William Bell, March Wind, Ruby Johnson, Mable John, Albert King and others.

In 1974 Stax Records was forced into involuntary bankruptcy by Union Planters Bank during their attempt to camouflage the bank’s improprieties. Deanie Parker would never give up on the Stax legacy.

Twenty-five years would pass before Memphians Sherman Wilmot, Howard Robertson, Staley Cates, Dr. George Johnson, Charles Ewing, Andy Cates, and Deanie Parker joined forces to help revitalize Soulsville USA with a museum, music academy and The Soulsville Charter School on the site where Stax Records was originally located. From 1998 until 2005, Deanie served as Soulsville’s first president & CEO.

She retired but returned as CEO from 2008 until Kirk Whalum came on board in 2010. The Stax Music Academy began programming in June 2000 and some of its early instructors were Rufus and Carla Thomas and Scott Bomar. The Stax Music Academy building opened in 2002 and the Stax Museum of American Soul Music opened the following year. The Soulsville Charter School began in 2005.

Today, the Soulsville Campus’ contributions to Memphis and the world are immeasurable. The Stax Music Academy has performed in Italy, Australia, Germany, France, England and at New York City’s Lincoln Center, most recently this past July with Booker T. Jones. The Stax Museum has drawn visitors from every continent. The Soulsville Charter School has had a 100% college acceptance rate since it began having graduations in 2012.

And, Soulsville has invested $40 million on the corner of College and McLemore, a place now that countless tourists and locals visit annually, where more than 100 employees and over 800 youngsters enjoy learning music and academics in an atmosphere based on the unique and timeless legacy of Stax Records.

“I didn’t realize how much Jim [Stewart] was despised for what he was doing. People couldn’t get over the fact that he was providing opportunities for black people who were being demeaned in every way that you could imagine. But, the Stax philosophy was a welcoming one. Jim and Estelle were not judgmental. Instead, they took the time to hear what it was we wanted to do, what we thought we could do and the commitments that we were prepared to make in order to make Stax better, to be part of an incredible organization that gave us this inimitable music.”

Be the first to add your voice.